Support Our Research : your contribution enables deeper research, richer content, and broader reach http://bit.ly/3TuqpHh

Alexander Was Not Dzulqarnain

This blog analyze the evidences that link Alexander the Great with Dzulqarnain . From the Syriac Alexander Legend, to Alexander's historical records

HirBenAli

6/1/2025

Not a single evidence that proves Alexander the Great was Dzulqarnain

If there is one evidence that the proponents of Alexander the Great was Dzulqarnain is the Syriac Legend Concerning Alexander/Syriac Alexander Legend/Neshana d-Alexksandros. It is claimed that the similarity of the theme and narrative in The Alexander Legend with the story of Dzulqarnain the Surah Al Kahfi proves beyond any doubt that Dzulqarnain was in fact none other than Alexander the Great.

The Syriac Alexander Legend is a supposedly 6th or 7th century legend detailing the exploits of Alexander the Great. The story of the Alexander Legend begins when Alexander summons his court to ask them about the outer edges of this world, for he wishes to go to see what surrounds it. His advisors warn him that there is a fetid sea, Oceanos (Oqyanos), like pus, and that to touch waters is death. Alexander is undeterred and wishes to go this quest. The summary of the Alexander plot as follows:

He prays to God, whom he addresses as the one who put horns upon his head, for power over entire earth

He stops in Egypt where he borrows 7000 blacksmiths of iron and brass from the king of Egypt to company his army

They set sail for four months and twelve days until they reach a fetid sea. Tested the water with condemned prisoners and they all die.

He goes to a place of bright waters and found the Window of the Heavens that the sun enters when it sets. Alexander follows the sun through its course to the east during the night and arrives at the mountain called Great Musas.

Also told that when the sun rises in the eastern land, the ground that to touch it to be burnt alive, so the people living there fleeing to the rising sun and hide in caves and in the water of the sea

Next Alexander travels north, evidently to Caucasus, until he comes to a place where there is a narrow pass. The locals complain of the savage Huns. The names of their kings include the Gog and Magog

Alexander built an iron and brass gate between the mountains with the help of the 7000 blacksmiths that he brought from Egypt

Alexander puts an inscription on the gate that contains a prophecy of events in the future

The first prophecy says that after 826 years, the Huns will break through the gate

The second one is, after 940 years there will come a time of sin and worldwide war. “The Lord will gather together the kings and their host”, he will give the signal to breakdown the wall, and the army of Huns, Persians, and Arabs will fall upon each other.

At the first glance, the theme and narrative of the Syriac Alexander Legend matches with Dzulqarnain story in the Surah Al Kahfi. And this similarity is used as the evidence that Dzulqarnain was in fact Alexander the Great. The assumption is, The Syriac Alexander Legend was an independent composition and might possibly pre-dating the revelation of the Surah Al Kahfi.

However, if we accept that the Syriac Alexander Legend was an independent composition and the theme and narrative was just happened to be similar to the Dzulqarnain story in the Quran, it implies that the Quran just copying and re-telling the Alexander Legend. Obviously as a Muslim this is unacceptable.

The Syriac text of the Alexander legend was notably edited and translated into English by E.A Wallis Budge in 1889, based on several manuscripts, often found alongside the Syriac Alexander Romance. The oldest surviving manuscript that we have today dates from 1708-1709 CE.

The vast majority of scholars give the dating of the Syriac Alexander Legend to 630 CE. That means the composition of the Syriac Alexander Legend was postdating the revelation of the Surah Al Kahfi . The surah Al Kahfi was revealed as an answer to the Jews’ inquiry in Makkah before 622 CE (most likely early in the Prophet’s saw career.

The fact remains is that the Legend only gives us the terminus a quo (first limiting point in time) and not anything concretes regarding its terminus ad quem (final limiting point in time). Since the Syriac Alexander Legend plainly mentions the existence of an Arab, its terminus a quo could be anywhere between 629 – 636 CE. The Arab kingdom was mentioned along side the Persian and Romans, so which Arabs kingdom that was. The only sensible options are:

1. The first Islamic State built by the Prophet saw

2. The Rashidun Caliphate

In conclusion, the Syriac Alexander Legend was composed somewhere between 628 -636 CE, with 636 being the terminus ad quem due to there being no explicit mention of the Arab conquest of Syria. However, to say exactly when the Legend came into being is impossible from historical viewpoint. The only definite conclusion is that this happened somewhere after 628CE.

The Islamic sources on the other hand make it clear that Surah Al Kahfi was revealed in Makkah sometime between 613-622 CE, most likely before 620 CE as the narration does not show any hostility form polytheist of Makkah toward the Prophet saw and it well known that the persecution reached its peak between 620-622 CE.

Therefore, to use the Syriac Alexander Legend as the proof that Dzulqarnain was indeed Alexander the great is baseless.

The Syriac Alexander Legend in itself does not exist in any manuscript form independently, but as an appendix of the Syriac Alexander Romance attributed to Callisthenes. All the extant manuscripts date from either the 18th century (earliest manuscript was written in 1708) or the 19th century. So, the integrity of the text is questionable. In the current state, we have no way of knowing how the text could have changed from its inception until 1708.The fact also that scholars fail to find the source of the Syriac Alexander Legend indicating that the Legend was an imagination of the author based on some oral sources and probably written sources in existence during the time of composition and attributed it to Alexander. The similarity in the theme and narrative with the story of Dzulqarnain implies that the Legend was influenced by it. It is not impossible to imagine either caravans from Makkah (pre-622 CE) or Madinah (post-622 CE) to Syria and sharing the stories of Dzulqarnain, especially with attribution of the gate (or barrier in the Islamic narrative) to Alexander from pre-existing sources and the author modifying it to fit his idea of the coming Apocalypse in the prophesy.

It is also possible that some of the Jews of Bani Nadir who lived among the Muslims and were exposed to Islam told of Dzulqarnain after expulsion in 625 CE. Furthermore, if one accepts the proposition that the Legend could have been composed between 630-636 CE, it is very likely that the Muslims themselves could have spread the Quranic narrative in Mesopotamia and southern Syria before the Syrian conquest starting in 636 CE.

One more important point to prove that the Syriac Alexander Legend was composed after the revelation of the Surah Al Kahfi is the silence of the Jews after the Surah was revealed. If the Syriac Alexander Legend was already in existence at that time, the Jews would have a point to accuse Prophet Muhammad saw just plagiarized the Syriac Alexander Legend. The silence proved otherwise. Even though the Syriac Alexander Legend has similar theme and narrative, there are several mistakes that shows the Legend was just the Christianized version of near eastern tales and attributed them to Alexander. The theme and narrative were influence by the Quranic Dzulqarnain.

Narrative Inconsistencies within the Syriac Alexander Legend:

1. The Blacksmith Anomaly

The Legend explicitly states that Alexander while in Egypt, brought along 3000 blacksmiths for bronze and 3000 for iron to company his army. Now, here is an interesting question. Who is in the right mind will bring along a massive number of blacksmiths on a military expedition as described in Syriac Alexander Legend? The inclusion of thousands of blacksmiths is funny and impractical when viewed through historical or military lens. It would just burden the army with non-combatants, slowing movement and straining supplies. It is assumed also that Alexander brought the material as well.

And remember the decision to bring along the 7000 blacksmiths while Alexander was still in Egypt. At this point the Gog and Magog or the construction of the gate is still not known and happens yet.

It looks like Alexander can see the future!

Where he needs the blacksmiths and the materials for the construction of the iron gate, even though he still does not know it yet. The Legend itself states that Alexander learned about the Gog and Magog, only after reaching the Central Asia, not while in Egypt. This contradicts the idea of bringing blacksmiths specifically for a gate he did not yet know he would need.

It seems likely that the blacksmiths were a narrative invention to explain the gate’s construction. It can be said that the Alexander Legend is just an expansion of the Quranic narrative. This is because, in the Quran, the building of the barrier is not mentioned in detail, so the author of the Alexander Legend in trying to explain and justify the construction of the iron gate, inserted the blacksmiths narrative in the Legend.

2. Geographic Contradictions

The Legend states that the location of the iron gate is in Caucasus mountain. Firstly, historically Alexander never reached the Caucasus.

Secondly, in the Quran it is explicitly stated that the journey to land of Gog and Magog was after the journey to the east, to the land of rising sun. This really contradicts the Quranic Dzulqarnain narrative. If we accept that Alexander was Dzulqarnain, then the location of the Yajuj and Majuj could not be at the Caucasus. If Alexander did reach the Caucasus, it happens way before the journey to the east. Again, this narrative was inserted just to explain the detail that was not in the Quran. It proves that the Syriac Alexander Legend was just a re-telling of the Dzulqarnain story in the Quran, with extra details added. The author just copying the Quran narrative with additional, fabricated details.

3.Barrier Description Mismatch

The barrier to imprison Gog and Magog was stated as an iron gate. Even though it was not stated in detailed the type of barrier that Dzulqarnain built, but it was definitely not a gate.

Probably the author was influenced by Josephus in his War of the Jews (c.75 CE), which states about a gate attributed to Alexander in the Caucasus region.

The Quran is explicit in its mention that the whole barrier was made of iron with copper poured in it. But it was definitely not a gate. The Alexander Legend goes into more detail, giving the dimension of the gate and likewise saying it was built from iron. The difference here is that the Quran is not explicit in saying that the barrier was a wall built into two mountains. The term saddayn is different from the word used for mountain(jibalayn), sadd is simply a barrier, whether natural or manmade, where is jibal is the Arabic word for mountain.

Another point to note is the Arabic word radm which is different from the word sadd. Sadd is a barrier as discussed before. However, the radm seems to imply either a more fortified barrier or something that would enclose Gog ang Magog completely

From the points above, it can be said that the Syriac Alexander Legend is not the definitive proof that Dzulqarnain was Alexander the Great. The supposed pre-Islamic mentions regarding Alexnder and the barrier all derive from post-Islamic manuscript. Even the mention of the gate attributed to Josephus Flavius in his Wars of the Jews (c.75 CE). The oldest manuscript of this book comes from the 9th century.The same also for the Jerome’s letter which is from the 8th century. Hence, we cannot close out the possibility that the later copyist of the works of Josephus and Jerome modified the text by attributing the gate to Alexander.

The other manuscript is the Alexander Romance. The mythical tale of his birth and his adventure. However, the oldest recension of the Alexander Romance (The Greek 3rd century recension) does not contain the gate episode. Only until 8th and 9th centuries, after the translation of the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius to Greek and Latin that the episode appears in the Alexander Romance. Hence the earliest form of the story that we have it in a verifiable form is in the Quran, followed by the Syriac Alexander Legend that was written some decades later.

The "Two Horns Attribution: A broader View

Does it prove that Dzulqarnain was Alexander the Great?

As for the claim that Alexander was known as the two-horned one, then we need to look at this from two angles.

Firstly, was Alexander extensively portrayed as having two horns in pre-Islamic history and was the attribution to him widespread?

Secondly, was Alexander the ONLY individual portrayed with two horns in ancient history?

The answer to both is no.

1. While we have coins and other artefacts of Alexander having two horns, most likely adopted after his conquest of Egypt from the god Zeus-Ammon, which was basically a fusion of Greek god Zeus and Egyptian gods Ra and Hamun, the attribution did not become widespread until well into middle ages. We have no evidence from any pre-Islamic recensions of Alexander Romance referring Alexander as the one with two horns, nor is there any evidence that this was widespread beyond his empire or that he was universally known as such. His more common portrayals emphasized youth and idealized features, like in scuptures and mosaics, without horns. Some more, it is inconceivable for Dzulqarnain to be associated with the pagan gods of Greek and Egypt.

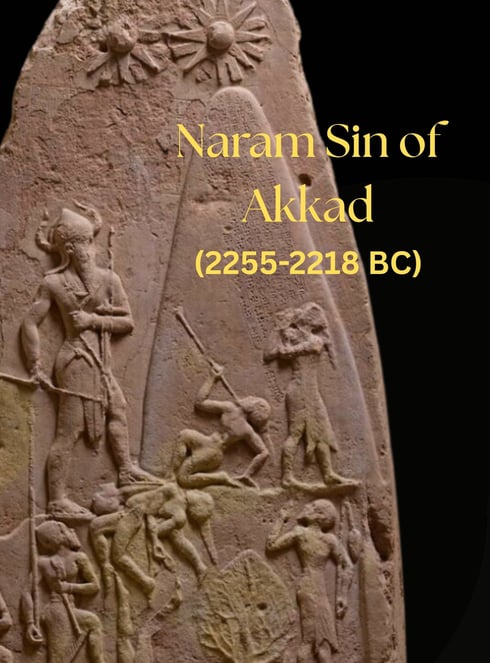

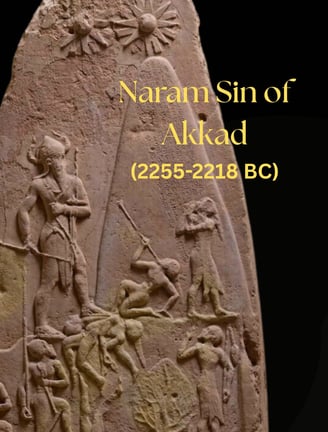

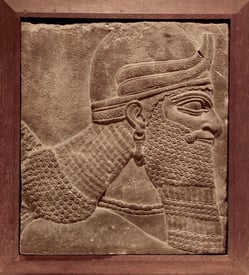

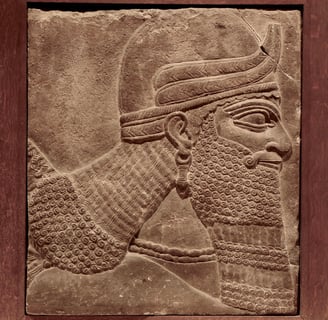

2. Alexander was far from being the only king who was portrayed with two horns in ancient history. In fact, it was a common motif among kings and rulers as horns signified power and rulership. One good example is Naram-Sin of Akkad (2255-2218 BC). The ruler of the Akkadian Empire and was the third successor and grandson of the King Sargon of Akkad. He is the first to claim the title “The King of the Four Quarters”. Possibly he is the inspiration for the saying that Dzulqarnain was a king from the time of Prophet Ibrahim as, since his lifetime was not that far from Prophet Ibrahim’s as. Other kings and rulers who were portrayed with two horns include Elamites who rule from roughly 2700 BCE, The Egyptian pharaohs, Seleucids, and even the Achaemenids in the form of Cyrus the Great.

The victory stele of Naram-Sin at the Louvre in Paris. It depicts King Naram-Sin of Akkad leading the Akkadian army to victory over a mountain people from the Zagros Mountains . Naram-Sin was depicted as having two Horns on his head gear

Alexander as Dzulqarnain from historical perspective

Previously, the discussion was based on the mythological Alexander, now let us see the evidence of Alexander was Dzulqarnain from the historical perspective.

Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) left a significant mark on history through his military campaigns and the establishment of Hellenistic cities. The primary surviving accounts of his life are by historians such as Arrian (Anabasis Alexandri), Plutarch (Life of Alexander), Diodorus Siculus (Bibliotheca historica, Book 17), Quintus Curtius Rufus (Historiae Alexandri Magni), and Justin (Epitome of the Philippic History). Additionally, lost works by contemporaries like Callisthenes, Ptolemy I ,Soter, Aristobulus, Nearchus, and Onesicritus provide insights through fragments and references in later texts

However, none of those historians ever recorded any episode of a construction of an iron wall. Building an impenetrable iron wall between two mountains is a massive construction project, and it is inconceivable that none of those historians fail to record it. So, the concept of “Iron gate” is only rooted in the myth rather than history.

Did Alexander the Great ever reach the Caucasus mountain or the surrounding area?

Alexander the Great's extensive military campaigns, spanning from 334 BCE to his death in 323 BCE, covered vast territories from Greece to northwestern India, raising the question of whether he reached the Caucasus Mountains or the surrounding area.

Research suggests that Alexander did not reach the modern Caucasus Mountains between Europe and Asia. His campaigns, as detailed in Britannica, focused on Persia, Central Asia, and India, with no historical evidence of military operations in the western Caucasus region.

The term "Caucasus Mountains" today refers to the mountain range between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, spanning modern-day Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and parts of Turkey and Iran. However, in ancient Greek sources, "Caucasus" had a broader application, often including the Hindu Kush mountains in modern-day Afghanistan, referred to as "Caucasus Indicus". Alexander the Great's legacy, extending beyond historical accounts into legendary narratives, includes references to the Gates of Alexander, a mythical barrier often associated with the Caucasus Mountains. Josephus Flavius, also known as Flavius Josephus, is a well-known Jewish historian from the 1st century AD, whose works include The Wars of the Jews and Antiquities of the Jews. These texts provide insights into Jewish history and interactions with Hellenistic figures, including Alexander the Great. The Gates of Alexander, a legendary construct, are mentioned in various ancient sources, including the Syriac Alexander Legend and the Qur'an, often linked to an iron barrier against barbarian tribes like Gog and Magog.

In the Josephus's writings, particularly The Wars of the Jews, and supplementary historical analyses.

Josephus's Mention of the Gate of Alexander

Research suggests that Josephus does mention the Gate of Alexander, specifically in The Wars of the Jews, Book VII, chapter 7, section 4. The passage, available at the Perseus Digital Library , states:

"Now there was a nation of the Alans, which we have formerly mentioned somewhere as being Scythians and inhabiting at the lake Meotis. This nation about this time laid a design of falling upon Media, and the parts beyond it, in order to plunder them; with which intention they treated with the king of Hyrcania; for he was master of that passage which king Alexander [the Great] shut up with iron gates."

This passage explicitly describes a passage shut up with iron gates by Alexander, later controlled by the king of Hyrcania, and used by the Alans to plunder Media. The Alans, identified as Scythians, were nomadic peoples inhabiting areas north of the Caucasus, such as near the lake Meotis (modern Sea of Azov), suggesting the gate was a barrier in the Caucasus region. The Syriac Alexander Legend also mention Alexander building an iron gate, specifically described as an iron and bronze wall, to seal off barbarian tribes. Legend states:

"Deciding to seal up their entryway through the mountains, he tasks his blacksmiths and metalworkers from Egypt to construct an iron and bronze wall". This wall is explicitly linked to containing Gog and Magog, aligning with apocalyptic themes common in the legend. The location of the iron gate, as described in the Syriac Alexander Legend, is in the Caucasus, specifically built as an apocalyptic barrier to keep out the nations of Gog and Magog. This is supported by the legend's context, where Alexander travels to Central Asia and sets up camp near a mountain pass, which is identified as the Caucasus in scholarly interpretations.

This interpretation is supported by the legend's connection to Persian fortifications and eschatological attitudes, with historical incursions like those by the Sabir people and Turkic Khazars in the 6th and 7th centuries corresponding to the predicted invasions mentioned in the Syriac Alexander Legend. These details suggest the Caucasus as a symbolic and strategic location for the iron gate, fitting the apocalyptic narrative.

Both, Josephus and the Syriac Alexander Legend put the location of the iron gate at the Caucasus mountain, but historically Alexander never reached that location, as historical Alexander did not campaign in the western Caucasus, focusing instead on Central Asia and India.

This discrepancy highlights the legendary nature of the Syriac Alexander Legend account, where historical facts are blended with myth,

With this , we can say that the Syriac Alexander Legend and Joshepus Flavius’s account cannot be taken as the evidence to prove Alexander the Great was Dzulqarnain in the Quran.

Alexander’s journey and Dzulqarnain’s journey comparison

In Quran, it is explicitly mentioned that Dzulqarnain reached the land of Yajuj and Majuj after his second journey. The sequence of the journey is mentioned clearly.

1.The West: He travels to a place where the sun appears to set in a murky spring. There, he encounters a people and is given the choice to either punish or treat them kindly. He chooses to reward the righteous and punish the wrongdoers, emphasizing justice (18:86–88).

2.The East: He reaches a place where the sun rises, finding a people with little protection from the sun. (18:89–90).

3.The Barrier: He arrives at a region between two barriers where a people, unable to understand his language, complain about the destruction caused by Gog and Magog (Yajuj and Majuj). Dhu al-Qarnayn builds a massive barrier of iron and copper to protect them, asking for no reward except their cooperation (18:91–98).

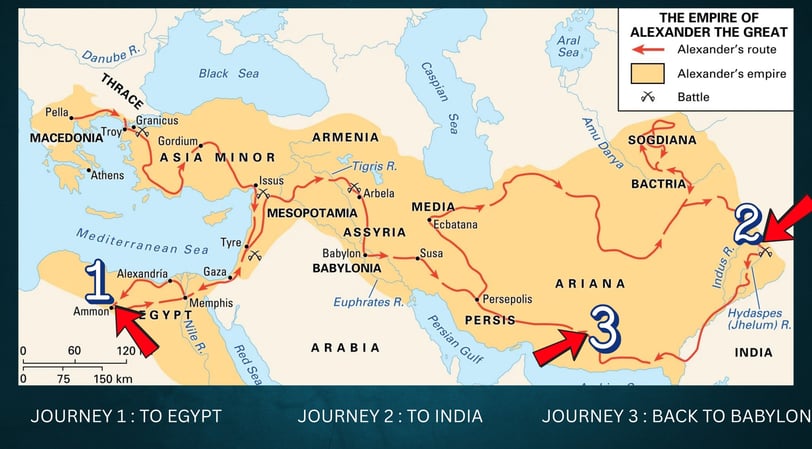

Comparison with Alexander’s journeys:

1. The west: His travel to Egypt

2. The East: His expedition to India. Hyphasis River (modern day Beas River) in Punjab, india

3. Returning to Babylon after his troops refused to go any further. From the Indus Valley through the Gendrosian Desert (modern Makran coast in southern Pakistan and southeastern Iran)

His third journey was problematic there. There was no way that Alexander encounter the land of Gog and Magog during his journey through the Gendrosian Desert.

There was no more expedition of Alexander after his return to Babylon. He died there at the age of 32

Clearly here the journey of Alexander did not match the journey of Dzulqarnain.

That is why, the proponents of Alexander as Dzulqarnain will never mention the expedition to India as the second journey. As the place where the sun rises. They will always locate the “the place where the sun rises, and people with no protection “before the Alexander journey to Central Asia, to Bactria and Sogdiana. Somewhere in Afghanistan

إِنَّا مَكَّنَّا لَهُۥ فِى ٱلْأَرْضِ وَءَاتَيْنَـٰهُ مِن كُلِّ شَىْءٍۢ سَبَبًۭا ٨٤

Indeed, We established him upon the earth, and We gave him from everything a way [i.e., means].

The word "sabab" translated as "a way", "means" or "cause" is interpreted expansively by Quranic commentators. It encompasses not only material resources such as might, armies, weaponry, and siege machinery necessary for conquest and governance, but also intangible assets like knowledge, wisdom, strategic understanding of lands and peoples, and the ability to plan and execute complex undertakings. Crucially, "sabab" also implies divine guidance and support, enabling him to achieve his objectives.

Now, does this Quranic verse, reflected in the Alexander's exploits? One of the episode in Alexander's life was the crossing of Gedrosian Desert on his return journey to Babylon. Arrian(Anabasis of Alexander) and Diodorus Siculus(Library of History) describe Alexander's crossing of the Gedrosian Desert in 325 BC, after his Indian campaign. Returning from Indus Valley, Alexander chose to march through the desert(modern Balochistan) to reach Babylon.

The crossing was catastropic: Harsh conditions (extreme heat, lack of water, sandstorms) led to massive losses.Estimates suggest 50-70% of his army (up to 60000 men, including soldiers and camp followers) perished due to hydration, starvation and exhaustion. Arrians notes Alexnader poor planning, underestimating the desert's challenges, and failing to secure adequate supplies, despite warnings from locals. The failure highlighted his overconfidence , a trait inconsistent with Dzulqarnain's humility and divine guidance.

Alexander's Gedrosian disaster is clear example of a failed campaign, contradicting the Quranic portrayal of Dzulqarnain as a ruler who effectively utilizes his "means" to succeed . This , combined with his paganism, and his unstable empire, strongly disqualifies him as Dzulqarnain

The map is showing the three journeys of Alexander the Great. The first journey was to Egypt, which could be considered as the journey to the West. The second journey to the East was supposed to be the to the most eastern part of his empire. Which was to the Hyphasis River in India . However his third journey might cause the theory of Alexander as Dzulqarnain to collapse. His third journey was returning back tu Susa/Babylon through the Gendrosa desert. There was of no possibility of him to encounter the land of Yajuj and Majuj through that desert

Alexander’s moral vs Dzulqarnain:

In the Quran, Dzulqarnain is depicted as a divinely guided king, morally upright, and wise. He is not corrupted by power that was given to him by God. He uphold the justice .

In contrast, Alexander’s historical campaigns were driven by imperial ambition, polytheism and domination. Known for military brutality, destruction of cities, and forced cultural assimilation. His action were often ego-driven and sought personal glory

Here are some of the brutality of Alexander as been recorded by historians:

1. The Plundering of Tyre (332 BCE)

After a seven-month siege, Alexander finally breached Tyre’s defences by constructing a massive causeway to connect the island city to the mainland. The final assault was brutal, and once inside, his forces committed widespread slaughter and plunder.

Details of the Plundering

Massacre of Tyrians:

According to Arrian (Anabasis II.24), about 8,000 Tyrians were killed in the initial assault.

Curtius Rufus (IV.4) claims that Alexander had 2,000 Tyrian defenders crucified along the shore.

Enslavement:

Diodorus Siculus (XVII.46) states that 30,000 men, women, and children were sold into slavery.

Looting:

The Macedonians plundered the city's wealth, including gold, silver, and luxury goods.

The Temple of Melqart (the Tyrian equivalent of Heracles) was looted but not destroyed.

Alexander made a sacrifice at the temple, possibly to associate himself with Heracles.

2. The Plundering and Burning of Persepolis (330 BCE)

After defeating Darius III, Alexander entered Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Persian Empire. Unlike his treatment of Babylon, which he spared, Persepolis was systematically plundered and then burned.

Details of the Plundering

Massive Looting:

Diodorus (XVII.71) estimates that 120,000 talents of gold and silver were seized from the royal treasury (equivalent to billions of dollars today).

Arrian (III.18) describes Alexander allowing his soldiers to freely plunder the city for several days.

Plutarch (Life of Alexander, 38) mentions the Macedonians loading their horses and camels with treasure.

The Burning of the Palace:

Curtius Rufus (V.7) describes how Alexander, possibly drunk, set fire to the palace of Xerxes.

Plutarch claims the idea came from Thais, a Greek courtesan, who allegedly urged Alexander to burn it down as revenge for the Persian burning of Athens in 480 BCE.

Arrian, however, suggests Alexander later regretted the act.

Enslavement and Massacre:

Many Persian nobles and women were enslaved.

Some accounts suggest that thousands of civilians were killed or displaced.

The ethical and moral portrait of Dzulqarnain sharply contrasts with the historically ruthless Alexander.

Conclusion: Assessing the Evidence

The identification of Alexander the Great with the Quranic figure of Dhul-Qarnayn lacks convincing evidence and faces significant contradictions on multiple levels:

Chronological: The primary textual evidence (Syriac Alexander Legend) postdates the Quranic revelation

Historical: Alexander's documented campaigns and character contradict the Quranic portrayal

Geographic: The proposed journey sequences and locations do not align

Moral: Alexander's historical brutality contradicts Dhul-Qarnayn's righteousness

Textual: Late manuscript evidence raises questions about the independence of non-Islamic sources

The evidence suggests that rather than the Quran borrowing from pre-existing Alexander legends, the reverse may be true: Christian and other traditions may have incorporated Islamic narratives about Dhul-Qarnayn into their Alexander legends during the early centuries of Islamic expansion.

This analysis does not definitively identify who Dhul-Qarnayn was, but it demonstrates that Alexander the Great is not a viable candidate. Future research should focus on other historical possibilities while maintaining rigorous standards for historical and textual evidence.

References

Ali, H. B. (2025). Alexander was not Dzulqarnain. Retrieved from https://merah-ungu.com/alexander-was-not-dzulqarnain

Arrian. (2nd century CE). Anabasis of Alexander.

Budge, E. A. W. (1896). The History of Alexander the Great: Being the Syriac Version of the Pseudo-Callisthenes. Cambridge University Press.

Curtius Rufus, Q. (1st century CE). Historiae Alexandri Magni.

Diodorus Siculus. (1st century BCE). Bibliotheca Historica, Book XVII.

Flavius Josephus. (75 CE). The Wars of the Jews. Book VII, Chapter 7, Section 4.

The Qur'an. Surah Al-Kahf (18:83-98).

Plutarch. (1st-2nd century CE). Life of Alexander.

Sukdaven, S., Mukhtar, M., & Fernana, A. (2015). Qissat Dhul Qarnayn: The Story of the Two-horned King. English translation of Timbuktu manuscript.

Yusuf Ali, A. (1934). The Holy Qur-an: Text, Translation and Commentary. Appendix on Dhul-Qarnayn.The Quranic account of the Dzulqarnain predates the Syriac Alexander Legend and other key texts that link Alexander to the gate of Alexander